The Vote Seller's Dilemma

Elections are the cornerstone of a thriving democracy, safeguarding our fundamental right to express our political will. They depend on citizens being able to cast their votes freely and independently, without coercion or bribery. Yet, the possibility of internet voting has sparked concern among some observers who note that its very verifiability and transparency could facilitate easier voter coercion or bribery.

In this digital age, the possibility of vote buying has become even more pronounced as potential buyers can be located far away, even beyond the reach of local law enforcement, and transactions can be automated. Despite these valid concerns, there are a large number of compelling reasons, that we have outlined here, suggesting vote selling may not be as significant a risk as some people fear.

Nonetheless, we present a legal solution based on Game Theory principles that makes the act of vote selling overwhelmingly risky. This proposal leverages the already substantial penalties for vote selling to disrupt trust between buyers and sellers, dramatically reducing the attractiveness of such illegal activities.

In addition to defending against internet vote selling, this solution also strengthens defenses for in-person and vote-by-mail as well.

Summary of Proposal

We suggest a solution to deter vote selling, inspired by the Prisoner's Dilemma from Game Theory. The core idea is to introduce a reward system where the one who reports the vote-selling scheme gets a portion of the hefty fine levied on the other party. For instance, if the offered price was $50, and one of the parties reports it, a fine of $5,000 could be imposed, and a $250 reward offered to the informer.

This system increases the risk and uncertainty in vote selling schemes. It discourages participation by making it more profitable to report the scheme than to stick with it. And to protect innocent people, the reporting party must provide solid proof, under penalty of perjury if they are lying, making the process fair and discouraging false accusations.

Detailed Proposal

Current Law

In the context of public government elections, vote selling is already a serious crime and has been in the US criminal code for over 70 years (18 U.S.C. §597 (opens in a new tab)), carrying up to 2 years jail time and a $10k fine for a single willful instance, for both buyer & seller.

With that said, although vote selling is illegal, it is hard to detect without one of the two parties revealing the scheme, and therefore hard to enforce laws against it.

If we can make vote selling easier to detect, we can enforce accountability and deter it in the first place.

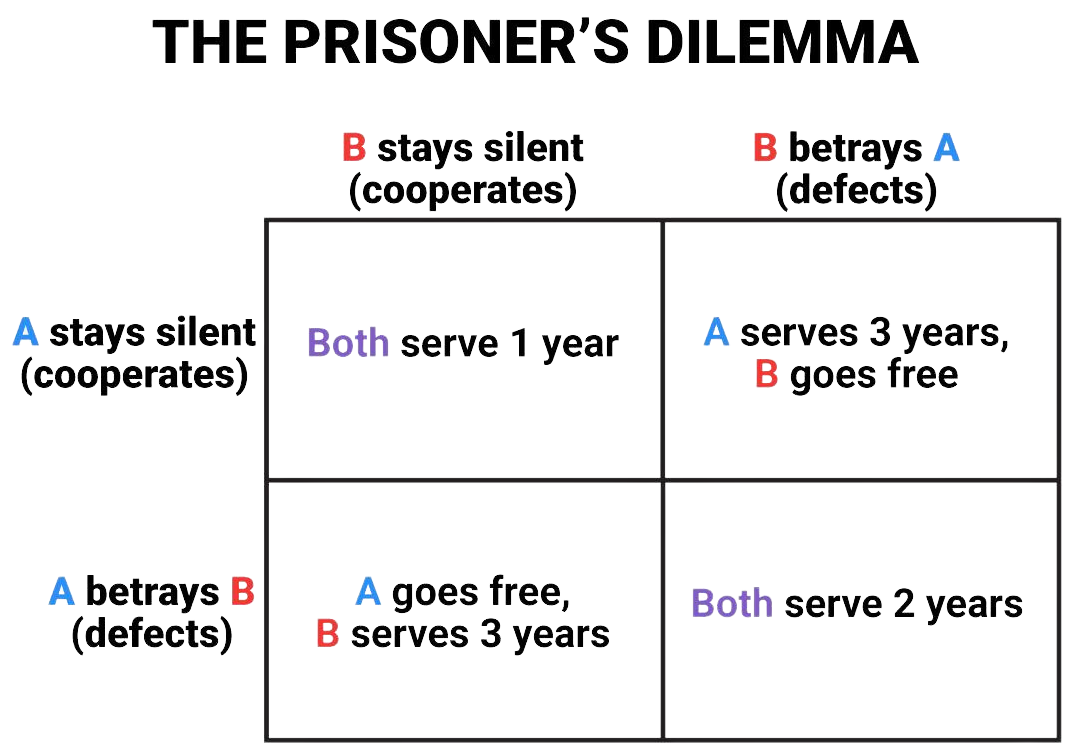

Standard Prisoner's Dilemma

The Prisoner's Dilemma illustrates how each player's individual interest — the “Nash equilibrium” — can be to always defect, no matter what action the other party takes.

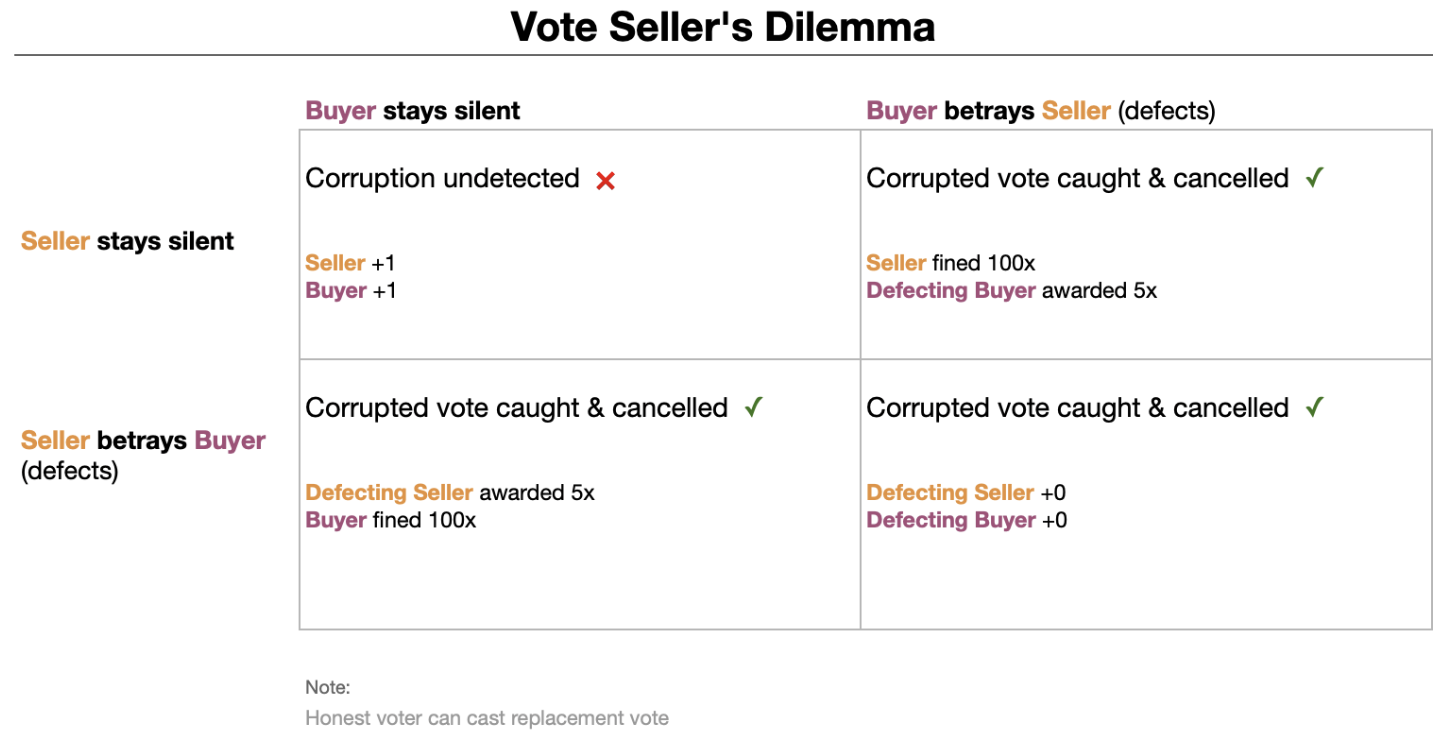

Vote Seller's Dilemma

In the context of vote selling, the two parties involved — the vote buyer and the vote seller — face uncertainty regarding mutual trust. As a result, both parties can be given a strong incentive to betray the other, revealing the vote sale.

This proposal suggests leveraging the substantial criminal penalties to generate a powerful incentive for either party to betray the other. Alongside jail time, governments could impose a fine equal to 100x the agreed-upon vote sale price.

A portion of the collected fine can be designated as a bounty reward for the party that exposes the vote-selling scheme. For example, if the buyer and seller agree to a price of $50, a fine of $5,000 could be imposed, with a $250 reward offered to the defector who reports the illicit transaction, if it leads to successful prosecution.

Such a setup introduces enormous risk for potential vote buyers and sellers, effectively deterring them from vote selling schemes.

To prevent false claims, accusers must provide verifiable proof and identify themselves. The requirement to identify themselves means they face perjury charges for false accusations. By verifiable proof we mean the kind of proof that verifiable internet voting enables in the first place. In other words, this proposal is specifically for the votes that are at new risk for vote selling because of internet voting.

Example Incentive Scheme

Agreed Upon Price = $P

Punishment if Caught = Fined $P × 100 + Jail time

Reward for Reporting = $P × 5

As with the Prisoner's Dilemma, it is consistently better for each party to betray the other. Both sides are aware that defection is also the better choice for their counterpart.

As a result, the ability of the two parties to trust each other is destroyed. Voters who might have considered selling their votes now face high risk of being caught in a honeypot, as the potential for deception and exposure is significantly high.

Even when the buyer is located outside the jurisdiction and may be more difficult to catch, the seller cannot be certain of this fact, as they could still be caught in a honeypot operation. Even in cases where the buyer can demonstrate their location outside the jurisdiction, they might still be motivated to collect the bounty reward instead. As a result, it is always better for the seller to betray the agreement rather than risk being betrayed themselves.

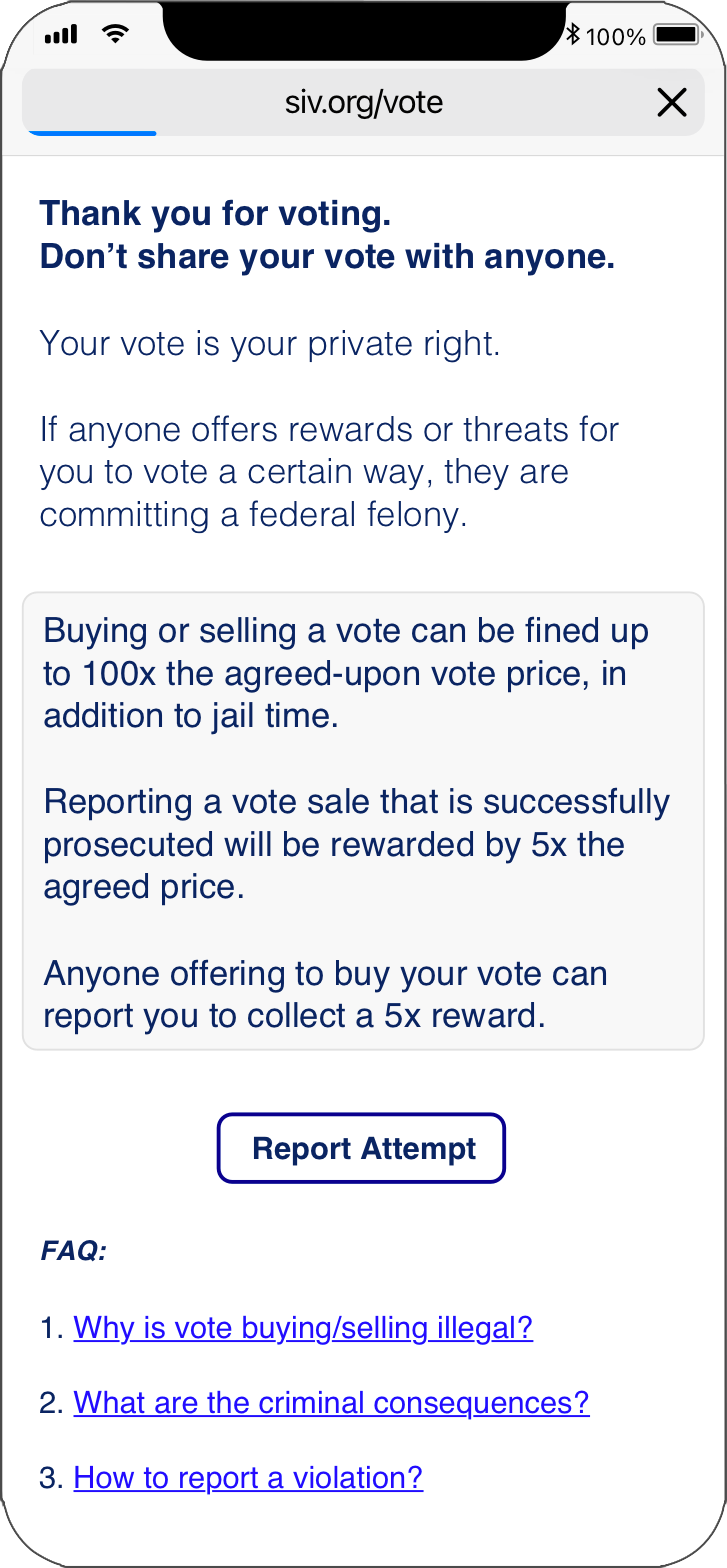

Promoting Integrity with SIV: Alerts and Guidance

The SIV voting software can warn voters about the legal consequences of selling their vote and the likelihood that any offers are a trap. By providing instructions on how to report any solicitations, SIV can actively discourage participation in such activities and promote a more honest voting process.

SIV Creates More Evidence of Vote Selling

In the case of selling a mail-in ballot, it is plausible that the corruption may not leave any tangible evidence. The seller could hand over a blank signed ballot in exchange for cash from the buyer, and both parties could part ways without leaving any trace of the transaction.

On the contrary, for SIV, if a voter attempts to sell their vote through a digital channel, there should be ample digital evidence available for either party to report the violation.

Thus SIV — when combined with the proposed strong incentives for reporting — can achieve even greater resistance to vote selling than mail-in voting.

Further Considerations

In the following sections, we cover several additional aspects and implications of the proposal:

A Solution for Government Elections

The game-theoretic defense against vote buying is tailored specifically for government elections, relying on the criminal justice system to enforce rules and collect fines.

For non-government elections, establishing a Nash equilibrium that favors defection could potentially be achieved by requiring voters to submit a substantial financial deposit when voting. This deposit could then be confiscated if any instances of vote selling are detected. But studying the details of this are out-of-scope for this proposal.

Forensic and Remedial Capabilities of SIV

Secure Internet Voting (SIV) has strong forensic and remedial capabilities. In the event of corruption, whether due to vote selling or otherwise, individual votes can be corrected at any stage. Compromised votes can be invalidated, and the final results retallied, regardless of whether the issue is identified before or after tallying the election results. If necessary, affected voters can be issued new ballots to recast their votes.

Although all votes are encrypted by default, a quorum of the election's Privacy Protectors can cooperate to selectively deanonymize an individual vote, while still protecting the privacy of all other voters. Discovered vote sellers cannot hide behind SIV's strong cryptography.

What this means is that vote sales can still be fixed and punished at any point. From a technical point of view, there is no time limit to catch them.

Enhancing Security for Mail-In and In-Person Voting

As mentioned in the Vote Selling section, both mail-in and in-person voting systems are not entirely immune to vote selling attempts. For mail-in voting, votes can be easily transferred by signing a blank ballot and handing it over or sending it through the mail. While in-person voting presents a greater challenge, it is still possible for voters to prove their choices by recording a video of a marked ballot being dropped into a ballot box using a smartphone camera.

The proposed strategy, which incentivizes both parties to defect, has the potential to not only mitigate vote selling attacks on internet voting systems, but also improve the security of mail-in and in-person voting methods.

Self-Sustaining Enforcement Mechanism

An attractive feature of the proposed framework is its self-sustaining nature: the 5x reward is derived from the 100x fine imposed on the party caught violating the rules. The remaining 95x should be sufficient to fund enforcement efforts. As a result, this framework offers a cost-effective approach to combating vote selling.

Self-Correcting Mechanism

The proposed framework automatically adjusts to match the amount of vote selling. If vote selling is a rare occurrence, enforcement costs remain minimal. However, if vote buying becomes more common, it generates a financial incentive for individuals to set up honeypots to capture vote sellers. In essence, this system is a self-correcting mechanism that adapts to the current situation.

On Foreign Interference

Part of the enforcement action comes from the ambiguity to would-be sellers about whether or not the buyer is actually a honeypot operation. For example, a prospective seller might come across a website stating to be based in a foreign jurisdiction and offering to purchase votes, only to discover that it is actually a local honeypot operation set up by their own neighbors.

One extreme scenario could involve the potential buyer providing irrefutable evidence of their complete immunity from the voting jurisdiction, thus eliminating all deniability. This could happen if a voter was absolutely certain that they were communicating with a known enemy of the jurisdiction, such as the dictator of a rogue nation. However, several factors must be considered:

-

To achieve this, they would have to relinquish all possible deniability, a move inconsistent with existing global cyberattack strategies and likely to result in severe negative public relations.

-

Adopting such a practice would be similar to a declaration of war against the targeted country's sovereignty, constituting an extreme measure that would not be taken lightly and is subject to its own forms of deterrence.

-

The enemy nation's leader could still choose to defect, such as to collect significant bounty rewards. This possibility means that even if they publicly identified themselves in an irrefutable way, that still does not give would-be sellers complete confidence their counterparty will protect their safety.

Examining Iterated Games

Individuals familiar with the Prisoner's Dilemma may identify a potential shortcoming in this approach when the problem is redefined as an Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma. Although both parties benefit more from defecting in any single round, successful cooperation for six consecutive rounds could yield more significant financial rewards than would be obtained by defecting in the first round. Nevertheless, several counterarguments can be presented to address this concern:

A. Neither party can confidently know that they are in the clear following the first round.

Their counterparty could be accumulating and collecting more evidence, with the possibility of defecting at any given moment.

The criminal statute of limitations can include vulnerability to all past violations, such that multiple 100x fines can easily overwhelm any financial reward they have received. In other words, even though it may look like both sides cooperated, they are still accumulating greater and greater liability and counterparty risk. Similarly, each counterparty is accumulating greater and greater possible bounty rewards for revealing the scheme.

There is a practical question of whether defecting long after an election should still result in bounty payouts. We suggest a reduced bounty in this situation, such as twice the original amount rather than five times, as it is preferable to detect violations before an election is certified. However, it is still valuable to maintain long-term incentives for either party to defect.

B. A counterparty may be cooperating in early rounds to establish a positive reputation, enabling them to attract a larger number of victims for later defection.

In summary, a counterparty's history of cooperation does not guarantee their continued cooperation in the future. Their incentive remains to feign cooperation initially and defect later when the potential payoff is greater. The possibility of a "long con" always exists.

Reversibility

We are confident in the robustness and viability of the proposed solution against vote selling and firmly believe in the many benefits of Secure Internet Voting. However, it is important to acknowledge that this proposal need not be infallible or guaranteed beyond any slightest doubt. If widespread coercion were to arise, internet voting can still be repealed, returning back to the status quo. Even in a hypothetical worst-case scenario in which electronic voting is entirely compromised by vote selling, a repeal can still be achieved by legislators, or by citizens in a paper-only referendum.

Therefore, the risk in adopting Secure Internet Voting is limited, providing a failsafe route back to paper-based voting methods.

We Have An Opportunity For End-to-End Verifiable Elections

Vote selling has long been a daunting challenge, particularly as we seek to integrate the convenience of Secure Internet Voting into our democratic process.

But the prospect of tackling this challenge is now achievable.

By implementing a robust legal framework that heavily penalizes vote selling through high fines and rewards to whistleblowers, we can undermine trust between potential vote buyers and sellers. This proposal does not just deter vote selling, it destroys the foundation it stands on.

Overall, by leveraging strong defense-in-depth practices and smart legislative frameworks, we can protect our democratic process, ensuring that every vote is free and fairly counted.